|

|

|

THE DIFFERENT

ARABIC VERSIONS OF THE QUR'AN

(Formerly entitled, "The Seven Readings of the Qur'an")

By Samuel Green |

Most of the Muslims I have spoken to boast about the Qur'an. One

of the common boasts that I have been told is that all the Qur'ans

in the world are identical, and that it is perfectly preserved and

free from any variation. This idea about the Qur'an is often said as

a way of attacking the Bible and trying to show that the Qur'an is

superior to the Bible. Consider the following quote from a Muslim

publication widely used in Australia.

No other book in the world can match the

Qur'an ... The astonishing fact about this book of ALLAH is that

it has remained unchanged,

even to a dot, over the last fourteen hundred years. ...

No variation of text can be found in it. You can check

this for yourself by listening to the recitation of Muslims from

different parts of the world. (Basic Principles of Islam,

Abu Dhabi, UAE: The Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahayan Charitable &

Humanitarian Foundation, 1996, p. 4, bold added)

The above claim is that all Qur'ans around the

world are identical and that "no variation of text can be found". In

fact the author issues a challenge saying, "You can check this for

yourself by listening to the recitation of Muslims from different

parts of the world". In this short article we take up this challenge

to see if all Qur'ans are in fact identical.

As God wills our investigation will be in three

parts:

- We will briefly examine

some history

related to the recitation of the Qur'an.

- Then we will

compare two

Arabic Qur'ans from different parts of the world.

- Finally, we will look at a

Qur'an that has

variant readings listed in its margin.

To start off our investigation let us begin by

reading the introduction to a translation of the Qur'an. N.J. Dawood

is an Arabic scholar who has translated the Qur'an, he writes:

... owing to the fact that the kufic script

in which the Koran was originally written contained no

indication of vowels or diacritical points, variant readings are recognized by Muslims as of equal authority. (N.J.

Dawood, The Koran, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books,

1983, p. 10, bold added)

According to this Arabic scholar there are variant readings of the Qur'an. But what is the nature of these

variant readings? To begin to answer this question we need to

realise that the Qur'an has been passed down to us from men called

"The Readers". They were famous reciters of the Qur'an in the early

centuries of Islam. The way in which the Qur'an was recited by each

of these Readers was formerly recorded in textual form by other men

called "Transmitters". The text made by a Transmitter is called a

"transmission" of the Qur'an. Thus a transmission is the Qur'an

according to a particular authoritative Reader. Any modern Qur'an

will be written according to one of these transmissions. You cannot

read the Arabic Qur'an except according to one of these

transmissions. Each of these transmissions has its own chain of

narrators (isnad) like a hadith. It is of interest to our

investigation to note that different transmissions are currently

used around the world today.

The following quote is from a Muslim scholar and

explains in a little more detail what I have said above:

(C)ertain variant readings existed and,

indeed, persisted and increased as the Companions who had

memorised the text died, and because the inchoate (basic) Arabic

script, lacking vowel signs and even necessary diacriticals to

distinguish between certain consonants, was inadequate. ... In

the 4th Islamic century, it was decided to have recourse (to

return) to "readings" (qira'at) handed down from seven

authoritative "readers" (qurra'); in order, moreover, to

ensure accuracy of transmission, two "transmitters" (rawi,

pl. ruwah) were accorded to each. There resulted from

this seven basic texts (al-qira'at as-sab', "the

seven readings"), each having two transmitted versions

(riwayatan) with only minor variations in phrasing, but

all containing meticulous vowel-points and other necessary

diacritical marks. ... The authoritative "readers" are:

Nafi` (from Medina; d. 169/785)

Ibn Kathir (from Mecca; d. 119/737)

Abu `Amr

al-`Ala' (from Damascus; d. 153/770)

Ibn

`Amir (from Basra; d.

118/736)

Hamzah (from Kufah; d. 156/772)

al-Qisa'i

[sic] (from Kufah; d. 189/804)

Abu Bakr `Asim (from Kufah; d. 158/778)

(Cyril Glassé, The Concise Encyclopedia of

Islam, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1989, p. 324, bold

added)

There are in fact many more Readers and

Transmitters than those listed above. The table below lists the

commonly accepted Readers and their transmitted versions and their

current area of use.

| The Reader |

The Transmitter |

Current Area of Use |

| "The Seven" |

| Nafi` |

Warsh Warsh |

Algeria, Morocco, parts of Tunisia, West Africa and

Sudan |

Qalun Qalun |

Libya, Tunisia and parts of Qatar |

| Ibn Kathir |

al-Bazzi |

| Qunbul |

| Abu `Amr al-'Ala' |

al-Duri al-Duri |

Parts of Sudan and West Africa |

| al-Suri |

| Ibn `Amir |

Hisham |

Parts of Yemen |

| Ibn Dhakwan |

| Hamzah |

Khalaf |

| Khallad |

| al-Kisa'i |

al-Duri |

| Abu'l-Harith |

| Abu Bakr `Asim |

Hafs Hafs |

Muslim world in general |

| Ibn `Ayyash |

| "The Three" |

| Abu Ja`far |

Ibn Wardan |

| Ibn Jamaz |

| Ya`qub al-Hashimi |

Ruways |

| Rawh |

| Khalaf al-Bazzar |

Ishaq |

| Idris al-Haddad |

|

There are even more Readers than these but these are

considered the most authoritative. The information

regarding the current area of use comes from Abu Ammaar

Yasir Qadhi, An Introduction to the Sciences of the

Qur'aan, United Kingdom: Al-Hidaayah, 1999, p. 199. |

What the above means is that the Qur'an has come

to us through many transmitted versions. Not all of these versions

are printed or used today but several are.

All these facts can be a bit confusing when you

first read about it. If you are feeling that way don't worry; it's

normal. To make things simple we will now look at two Qur'ans from

different parts of the world which are printed according to two

different transmissions. We will compare two Qur'ans to see whether

or not they are identical as the Muslim quote referred to at the

beginning of this article claimed. The Qur'an on the left is the

most commonly used Qur'an and is according to the Hafs'

transmission. The Qur'an on the right is according to the Warsh'

transmission and is mainly used in North Africa.

|

When you compare these Qur'ans it

becomes obvious that they are not identical. There are

three main types of differences between them.

- Graphical/Basic letter

differences

- Diacritical differences

- Vowel differences

|

|

Let us now look at examples of these differences.

The following examples are from the same word in the same verse,

however, you will notice that on some occasions the verse number

differs between the two Qur'ans. This is because the two Qur'ans

number their verses differently. Thus surah 2:132 in the Hafs Qur'an

is the same verse as surah 2:131 in the Warsh Qur'an.

GRAPHICAL/BASIC LETTER DIFFERENCES - There

are differences between the basic printed letters of these two

Qur'ans. It was these letters that Uthman standardized in his

recension of the Qur'an [1].

| THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO THE TRANSMISSION OF IMAM

HAFS |

THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO THE TRANSMISSION OF IMAM

WARSH |

surah 2:132 (wawassaa) |

surah 2:131 (wa'awsaa) |

surah 91:15 (wa

laa yakhaafu)

|

surah 91:15 (fa

laa yakhaafu) |

surah 2:132 (himu) |

surah 2:131 (hiimu)

|

surah 3:133 (wasaari'uu) |

surah 3:133 (saari'uu) |

surah 5:54 (yartadda) |

surah 5:56 (yartadid) |

The above examples show that there are differences between the

basic letters of these two Qur'ans.

DIACRITICAL DIFFERENCES - Arabic uses dots

to distinguish between certain letters that are written the same

way. For instance the basic symbol

represents five different

letters in the Arabic language depending upon where the diacritical

dots are placed. For the above example, the five letters with their

diacritical dots are as follows: represents five different

letters in the Arabic language depending upon where the diacritical

dots are placed. For the above example, the five letters with their

diacritical dots are as follows:

baa', baa',

taa', taa',

thaa', thaa',

nuun, nuun,

yaa'. However these dots

were a later development of the Arabic script and were not in use

when Uthman standardized the text of the Qur'an. Thus the Uthman'

Qur'an did not have any dots to record the exact letter and

pronunciation. The text could be read in several ways and was in

this way ambiguous in places. It served as a guide for the different

Readers of the Qur'an, but not as a complete guide because the

diacritical dots were not yet in use. The two Qur'ans that we are

examining come from two different Readers and so have two different

oral traditions. These traditions have their own unique system of

where the dots (and vowels) should go. Here we see another

difference between these two Qur'ans for they do not have the dots

in the same place. We see that for the same word these two Qur'ans

have the dots in different positions thus making different letters.

(Remember that verse/aya numbering differs between these two

Qur'ans.) yaa'. However these dots

were a later development of the Arabic script and were not in use

when Uthman standardized the text of the Qur'an. Thus the Uthman'

Qur'an did not have any dots to record the exact letter and

pronunciation. The text could be read in several ways and was in

this way ambiguous in places. It served as a guide for the different

Readers of the Qur'an, but not as a complete guide because the

diacritical dots were not yet in use. The two Qur'ans that we are

examining come from two different Readers and so have two different

oral traditions. These traditions have their own unique system of

where the dots (and vowels) should go. Here we see another

difference between these two Qur'ans for they do not have the dots

in the same place. We see that for the same word these two Qur'ans

have the dots in different positions thus making different letters.

(Remember that verse/aya numbering differs between these two

Qur'ans.)

| THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO THE TRANSMISSION OF IMAM

HAFS |

THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO THE TRANSMISSION OF IMAM

WARSH |

surah 2:140 (taquluna) |

surah 2:139 (yaquluna) |

surah 3:81 (ataytukum) |

surah 3:80 (ataynakum) |

surah 2:259 (nunshizuhaa) |

surah 2:258 (nunshiruhaa) |

From the above examples we can see that there are

many dots that are different between these two Qur'ans. The

oral traditions are not the same.

VOWEL DIFFERENCES - In the Arabic script

of the modern Qur'an the vowels are indicated by small symbols above

or below the basic printed letters. Like the diacritical dots, these

vowel symbols were a later development in the Arabic script and were

not in use when Uthman standardized the text of the Qur'an. Thus the

vowels too were not written in the Uthman' Qu'ran. With the vowels

we see another difference between these two Qur'ans, for on many

occasions they do not have the same vowels used for the same word.

Consider the following examples of how the vowels differ between

these two Qur'ans.

| THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO THE TRANSMISSION OF IMAM

HAFS |

THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO THE TRANSMISSION OF IMAM

WARSH |

surah 2:214 (yaquula) |

surah 2:212 (yaquulu) |

surah 2:10 (yakdhibuuna) |

surah 2:9 (yukadhdhibuuna) |

surah 2:184 (ta'aamu

miskiinin) |

surah 2:183 (ta'aami

masakiina) |

surah 28:48 (sihraani) |

surah 28:48 (saahiraani) |

Some Muslims claim that the differences between the diacritical

dots and the vowels are not the result of the ambiguity of the

Uthman' text but that the "accepted variants" are all part of the

revelation of the Qur'an. Thus there is not one way to recite the

Qur'an but many ways - many different oral traditions. Other Muslims

though disagree with this; they say there is only one way to recite

the Qur'an and that the variants come from The Readers [2].

Regardless of the answer to this question the fact remains that

there are real differences between these two Qur'ans and that is

what we are considering in this article. There are differences in

the basic letters, diacritical dots, and vowels. These differences

are small, but they do have some effect on the meaning.

The following is a summary from a scholar who has

done a more comprehensive study of this than I have. Again he is

only comparing two of the many transmissions:

Lists of the differences between the two

transmissions are long, ... (however) The simple fact is that

none of the differences, whether vocal (vowel and diacritical

points) or graphic (basic letter), between the transmission of

Hafs and the transmission of Warsh has any great effect on the

meaning. Many are differences which do not change the meaning at

all, and the rest are differences with an effect on meaning

in the immediate context of the text itself, but without any

significant wider influence on Muslim thought. One difference

(Q. 2/184) has an effect on the meaning that might conceivably

be argued to have wider ramifications. (Adrian Brockett, `The

Value of the Hafs and Warsh transmissions for the Textual

History of the Qur'an', Approaches to the History of the

Interpretation of the Qur'an, ed. Andrew Rippin; Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1988, pp. 34 and 37, bold added)

Our investigation so far has only considered two

transmissions of the Qur'an but as we saw at the beginning of this

article there are many more transmissions that could also be

examined for variants. The book below has done just that. It is a

collection of variant readings from The Ten Accepted Readers.

Translation

|

Making Easy the Readings of What Has Been Sent Down

Author

Muhammad Fahd Khaaruun

The Collector of

the 10 Readings

From al-Shaatebeiah and al-Dorraah and al-Taiabah

Revised by

Muhammad Kareem Ragheh

The Chief Reader

of Damascus

Daar Beirut |

In this edition of the Qur'an Muhammad Fahd

Khaaruun has collected variant readings from among The Ten Accepted

Readers and included them in the margin of the Qur'an (Hafs'

transmission). These are not all the known variants. There are other

variants that could have also been included but the author has

limited himself to the variants of The 10 Accepted Readers. As the

title of his book suggests this makes it easy to know what the

variant readings are because they are clearly listed with the text

of the Qur'an.

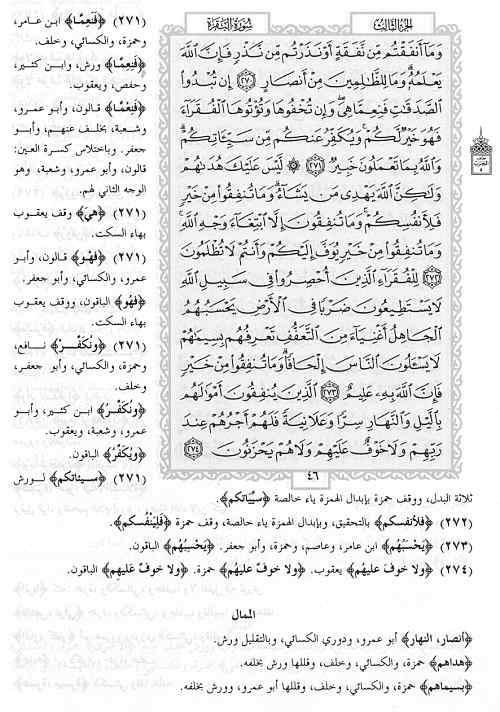

Below is a copy of a random page from this

Qur'an. You can see the variant readings listed in the margin. About

two thirds of the ayat (verses) of the Qur'an have some type of

variant.

I am often told by Muslims that the differences

between the different Qur'ans are only a matter of pronunciation.

However this is not the case. Subhii al-Saalih is an Islamic scholar

in this area. He summarizes the differences into seven categories

[3].

- Differences in grammatical indicator (i`raab).

- Differences in consonants.

- Differences in nouns as to whether they are

singular, dual, plural, masculine or feminine.

Differences in which there is a substitution of one

word for another.

- Differences due to reversal of word order in

expressions where the reversal is meaningful in the Arabic

language in general or in the structure of the expression in

particular.

- Differences due to some small addition or

deletion in accordance with the custom of the Arabs.

- Differences due to dialectical

peculiarities.

What is clear from this list is that the

differences are more than just differences in pronunciation.

CONCLUSION. We began this article by

considering the following quote from a Muslim organisation about the

Qur'an:

No other book in the world can match the

Qur'an ... The astonishing fact about this book of ALLAH is that

it has remained unchanged,

even to a dot, over the last fourteen hundred years. ...

No variation of text can be found in it. You can check

this for yourself by listening to the recitation of Muslims

from different parts of the world. (Basic Principles of Islam,

Abu Dhabi, UAE: The Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahayan Charitable &

Humanitarian Foundation, 1996, p. 4, bold added)

I have checked this claim for myself by obtaining

Qur'ans from different parts of the world and comparing them to see

if they are absolutely identical. What my research has revealed is

that the above claim about the Qur'an is wrong. The Qur'ans of the

world are not absolutely identical. There are small differences in

the basic letters, diacritical dots, and vowels. In fact there are

Qur'ans which list these variants in their margin. This means that

how the Qur'an is recited in different parts of the world is also

not absolutely identical. Since the Qur'an has variation within its

text and oral tradition it is not superior to the Bible. Please do

not make or believe such exaggerated claims about the Qur'an.

Endnotes:

[1]

How and Why

Uthman Standardized the Qur'an.

[2]

The Origin of the

Different Readings of the Qur'an.

[3] Subhii al-Saalih,

Muhaahith fii `Ulum al-Qur'aan, Beirut: Daar al-`Ilm li al-Malaayiin,

1967, pp. 109ff.

Related Reading:

Qur'anic textual

criticism - A comparison between the Samarqand MSS and the modern

version of the Qur'an.

The author welcomes

your response via

email

Christian-Muslim Discussion Papers © 2005

Further

Discussion Papers by

Samuel Green

The

Text of the Qur'an

Answering Islam Home Page

|

|

|